This blog is part of a series of articles meant to progressively understand how election data can be used to predict future outcomes. I will add to this site on a weekly basis under the direction of Professor Ryan D. Enos. In the run-up to the midterm elections on November 8, 2022, I will draw on all I have learned regarding what best forecasts election results, and I will predict the outcome of the NE-02 U.S. Congressional Election.

House of Representatives Election Data Analysis

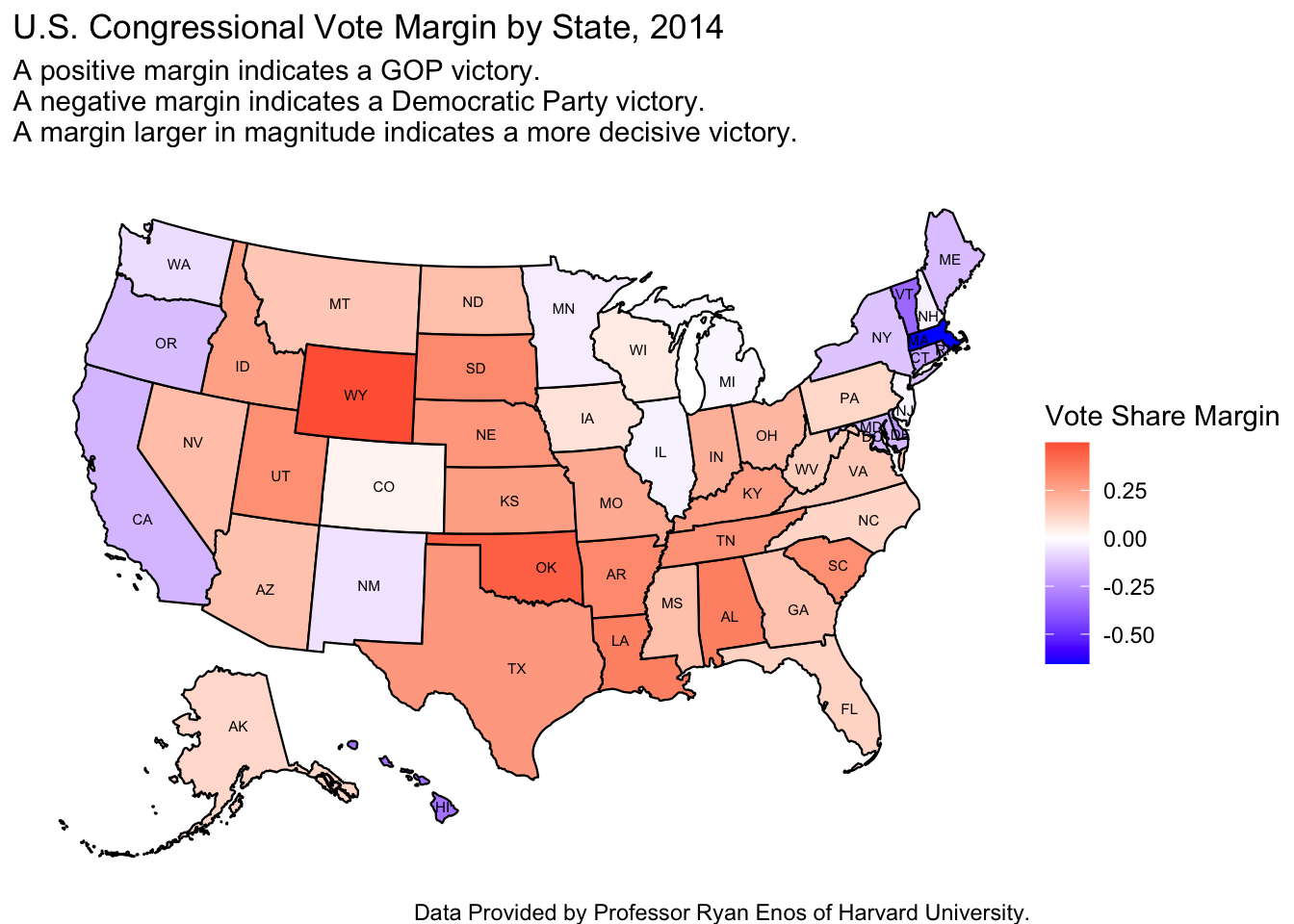

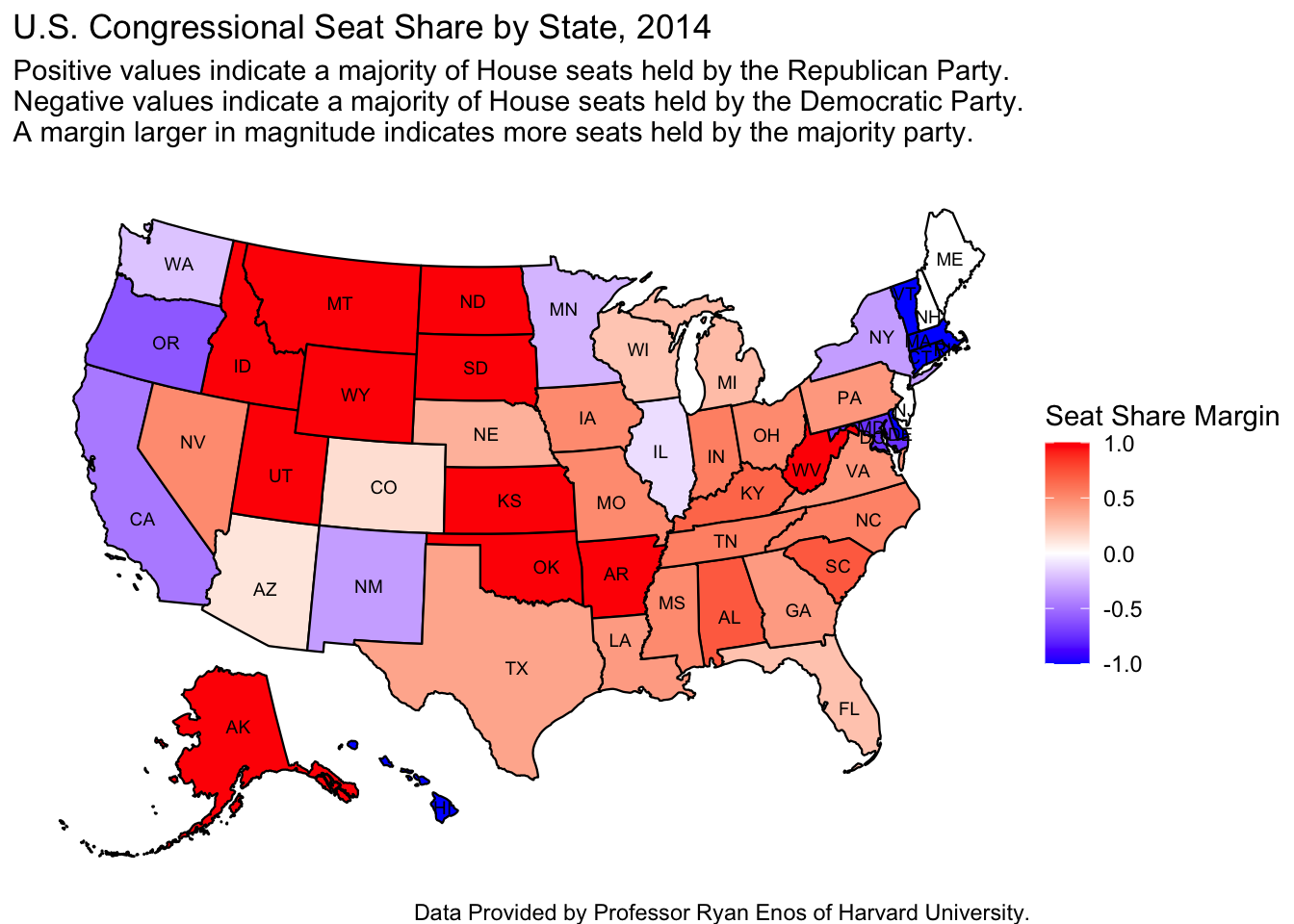

In this inaugural blog, I am examining data on elections for the U.S. House of Representatives in the 2010’s in order to better see how it can translate into an effective model for the 2022 midterm elections. A prominent question is how we can look at vote share margins and seat shares in congressional districts and use that data as a baseline to predict future election outcomes. By witnessing trends over time in a district’s vote share margins and the capability of a district to elect an official of a certain party, one can plausibly predict the direction where that district is headed in the future.

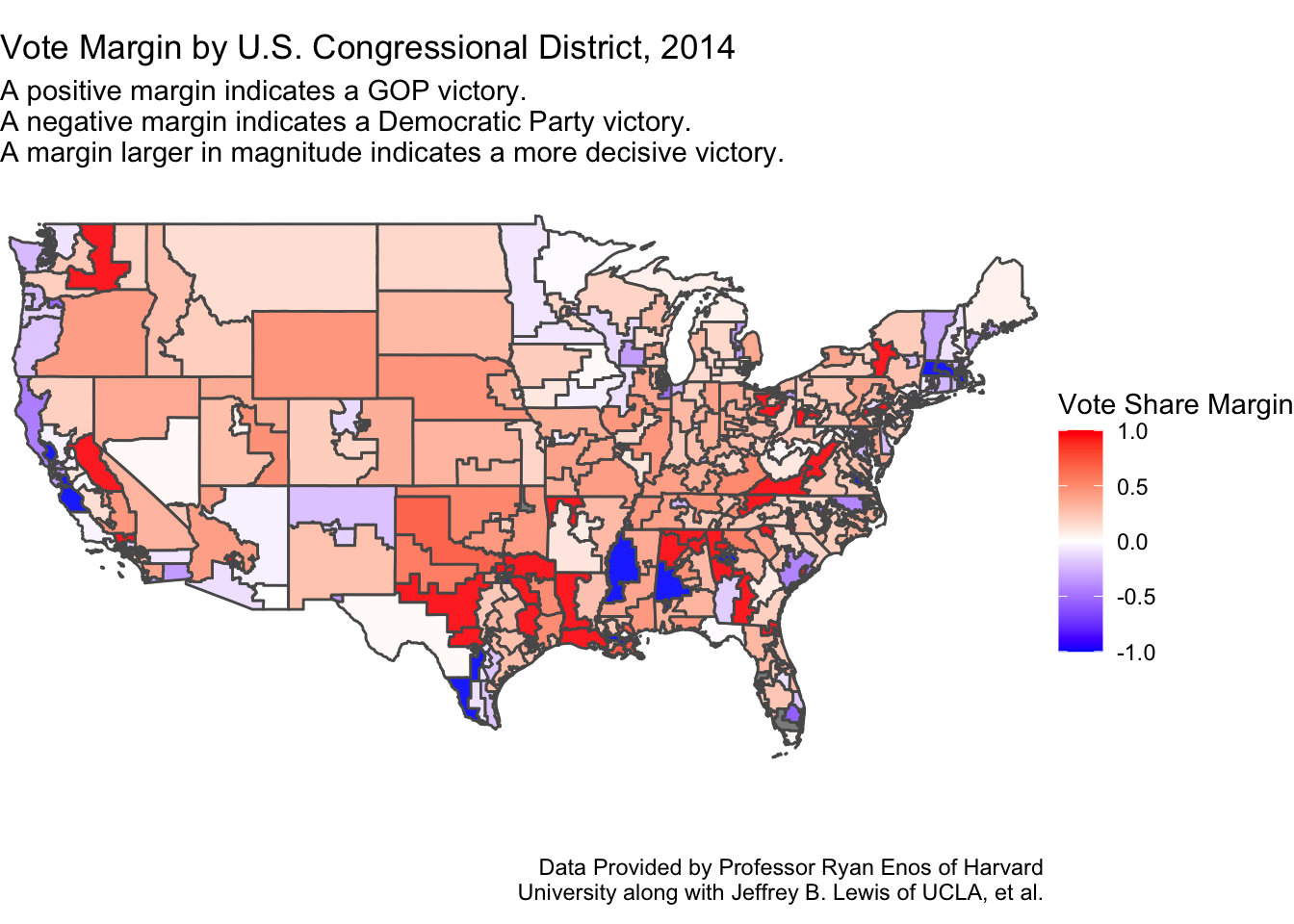

Vote Margin by U.S. Congressional District

Here we can further take a peek into how Democrats and Republicans perform on a district level. Oftentimes districts lack competition between the parties because of gerrymandering that works to assist a political party by lessening their probability of being defeated in the general election by the candidate of the opposing party. Gerrymandering often leads to heated primaries between members of a party since there is not as large of an incentive to win over independents or members of the opposing party, of which there are so few. From the previous visaulization, it would be easy to deduce that states with a large GOP vote share margin like Alabama would not elect a Democrat as a representative for their delegation to the House. However, upon examining Alabama on a district-level, we can see they did elect a Democrat in 2014 with strong enthusiasm. Gerrymandering is one way you can explain this: when the new district maps were being drawn, the GOP-sided officials in charge acknowledged there were a fair share of Democrats residing in the west side of Alabama. Instead of dispersing them across many districts, and allowing Republicans to become potentially more vulnerable in them, the GOP conceded only one district to the Democrats, thus saving the many others for themselves. Examining how these districts change in shape and in how voters vote over time can be a great insight into future outcomes.

Relating Back to Nebraska’s 2nd Congressional District

Nebraska’s Living Bipartisanship

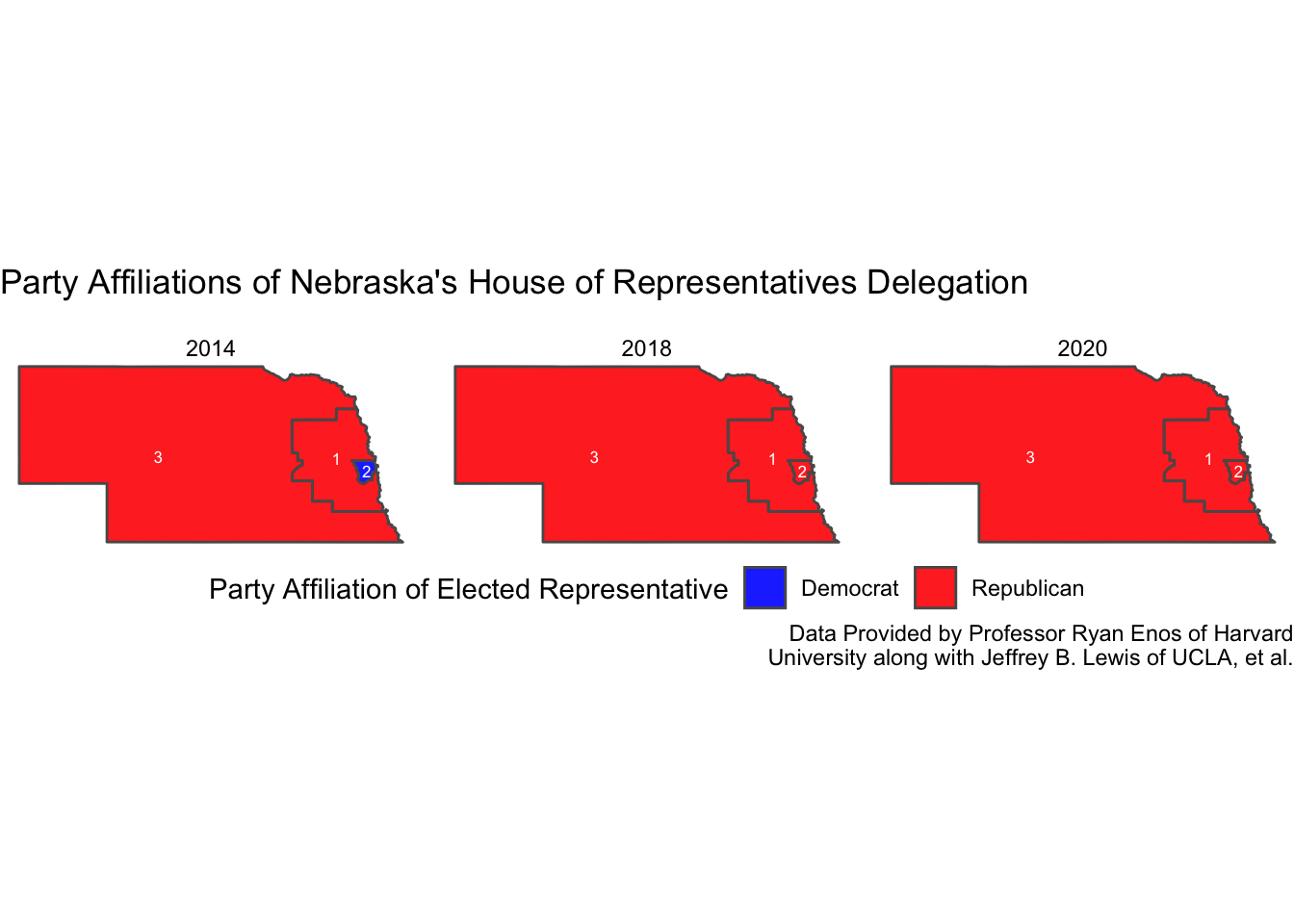

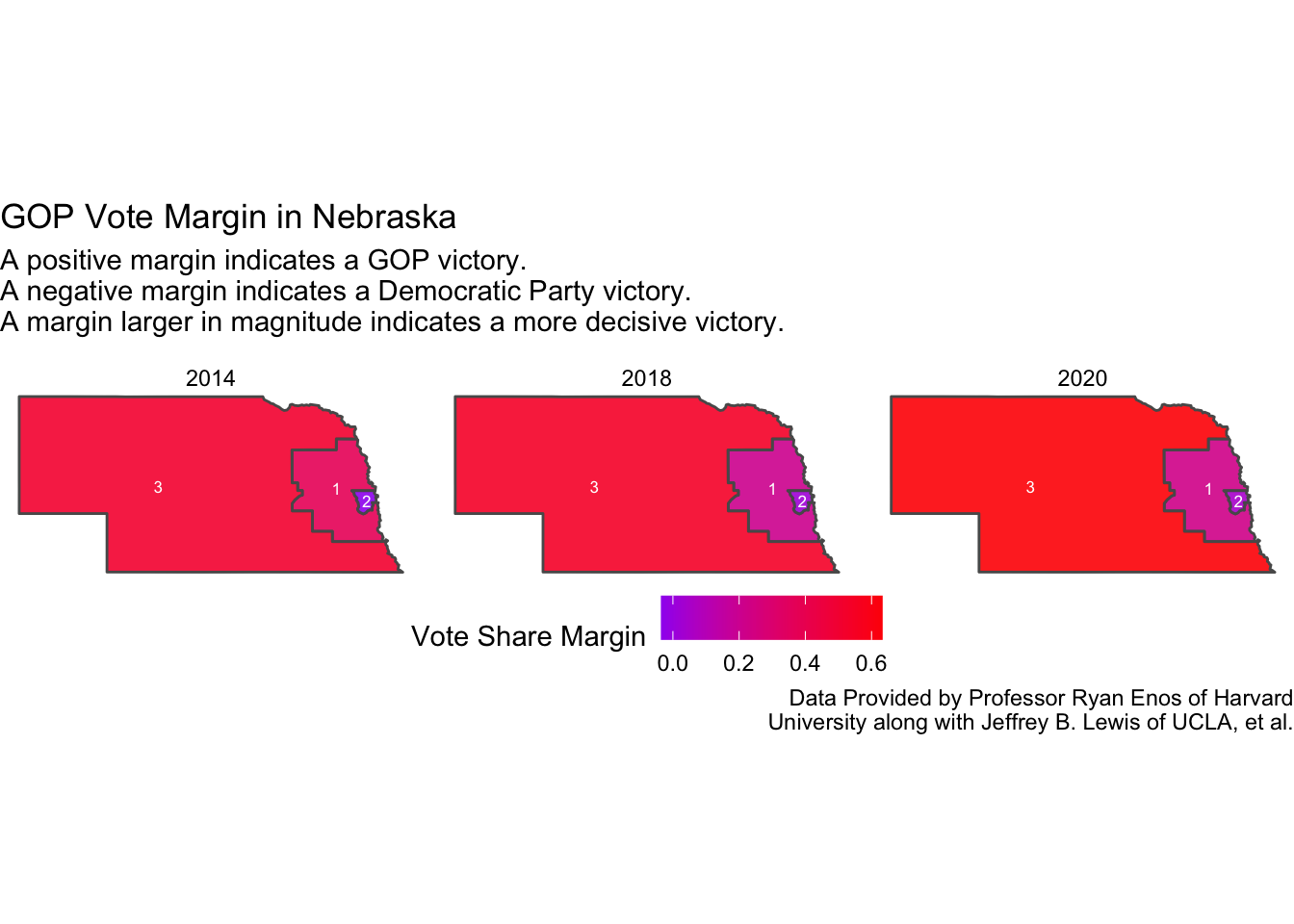

The culmination of my work over the next two months will result in a prediction of the election in Nebraska’s 2nd Congressional District (NE-02). Thus, I would like to discuss Nebraska particular situation regarding vote share margins and seat shares. In the visualizations below, I have included data from 2014 (to compare to those above), 2018 (the most recent midterm election), and 2020 (the most recent voting data).

As of recently, Nebraska has garnered a public reputation of being a dependable state for the GOP. In the visualizations below, it is not hard to understand why that is — especially when Nebraska has had 2 Republican senators throughout this time period as well. However, just under a decade ago, Nebraska had a Democratic senator, and as the visualization displays, a Democratic representative from NE-02. In this district lies Nebraska’s foremost urban city, Omaha, and its sprawling suburbs, an environment becoming increasingly favorable to Democrats nationwide. While NE-02’s Democratic elected official only lasted one term in office after his election in 2014, this phenomenon proved once more that there is potential for a Democrat to emerge from Nebraska.

Nebraska’s Urban-Rural Divide

A common sight across the United States is how rural areas are sprinting toward the GOP while the urban and suburban spheres are huddling around the Democratic Party. In Nebraska, that seems to ring true, according to their vote share margin trends. In NE-01 lies Nebraska’s capital city, Lincoln, with around 300,000 people. The vast majority of Nebraska’s rural land constitutes NE-03, which presents an interesting case of gerrymandering, where this district’s trend of an increasing GOP vote share margin almost guarantees a GOP win each cycle.

A look into NE-01 shows a suprisingly rapid realignment in favor of the Democratic Party: almost cutting in half their 40 point margin deficit in 4 years. This still leaves the district with a 2 election streak of a GOP victory by more than 20 points, signifying that a Republican still ought to be heavily favored solely on party affiliation.

NE-02 is where promise shows for Nebraskan Democrats. In addition to winning in 2014, the Democrats were able to sustain their close competition in the district over the next 6 years, eventually delivering one electoral vote to now-President Joe Biden. By looking into NE-02’s history with their representative’s party affiliation and vote share margins, it is not at all evident that one party is overly favored to win this district every two years. While that is not a prediction in favor of any one party or candidate, it does help to rule out the phenomenon of “one party rule” that has infected many districts across the country. Through this data analysis, I am led to believe that this district contains a competitiveness that gives a Democrat in Nebraska a real avenue toward a groundbreaking win. In the currnet political environment that revolves around an unpopular incumbent Democratic president in his fist term, a struggling economy, and abortion rights, this district will be a fantastic way to learn about how voters behave.

Sources:

Jeffrey B. Lewis, Brandon DeVine, Lincoln Pitcher, and Kenneth C. Martis. (2013) Digital Boundary Definitions of United States Congressional Districts, 1789-2012. Retrieved from https://cdmaps.polisci.ucla.edu on [09-15-2022].

House general elections, All States, 2014 summary. (2022). CQ voting and elections collection (web site). http://library.cqpress.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/elections/avg2014-3us1