In this blog, I have produced my final prediction for the upcoming Fall 2022 Midterm Elections. After exploring potential variables that can influence my predictions for how Democrats will fare and refining those variables, I have finalized my current models for the national-level prediction and the district-level predictions. First, I will explain how my models work, and I will justify why I included the variables that have been inputted. Next, I will interpret how my models perform and put them through a test to validate their effectiveness. Lastly, I will plot and display my predictions and their predicted ranges.

My Predictive Variables

Below, I am going to list my predictive variables and the reasons for which I am using them. In each model that I will examine subsequently, not all of these variables will be used, and I will discuss those reasons when I arrive at that model.

Incumbency

I have two variations for this variable:

- On a national-level model, I will use the total number of incumbents running for re-election for the House of Representatives.

- On a district level model, I will denote whether or not the incumbent is running for re-election in the specific district.

This variable can be a crucial predictor, as I have examined in a previous blog post and as Professor Ryan D. Enos has explored in Gov 1347 Lecture, because incumbents who decide to run for re-election only lose about 5% of the time. This has proven to be a great predictor of victory for an incumbent.

Party Control of the House of Representatives

With political experts floating the notion that undesirable governing outcomes (like high inflation) motivate voters to eject the party in power, I included a variable that indicates what happens to the vote share or seat share when the Democrats hold the House in an election.

Party Control of the White House

In the same vein, I have included a variable that affects vote share or seat share when a Democrat holds the keys to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. After all, research shows that many voters tend to punish the incumbent president’s party when they feel he has not performed the job well.

Whether or Not There is a Presidential Election

Here I control for whether the congressional elections are accompanied by a presidential election. I have explored in a previous blog post that if it is a midterm cycle (no accompanying presidential election), vote share and seat shares can be drastically affected.

Mean Democratic Party National Generic Ballot Margin

Here is an interesting variable that accounts for two factors I explored in my polling blogpost:

- Voters hold a recency bias

- Aggregate polls perform better than standalone polls that contain potential bias toward one side

Therefore, I have created a variable that contains an aggregate mean of all generic ballot (Democrats vs Republicans on a nationwide level) polls conducted within 50 days of an election. Assuming the polls are accurate and predictive, this variable factors that people vote on their recent feelings (also giving enough time to account for people voting early) and that polling aggregates converge on the actual result as you get closer to an election. Thus, I employed RealClearPolitics’ Current Aggregated Generic Congressional Ballot, where Democrats are down 2.5 points to the Republicans.

Expert Ratings (Only for District Model)

Lastly, I have included an aggregate mean (for the same reasons above: eliminate bias and wisdom of the crowd) of the expert ratings from various professional outlets: FiveThirtyEight, Cook Political Report, and Inside Elections.. As we will see, these ratings on whether a district is noncompetitive or a toss-up between the different parties are potent predictors. However, some of these ratings are also based off variable I have used above and off fundamental indicators (like the economy), so maybe it is cheating. However, I believe it makes my model more robust, which is the goal. Always have to use your resources, am I right?

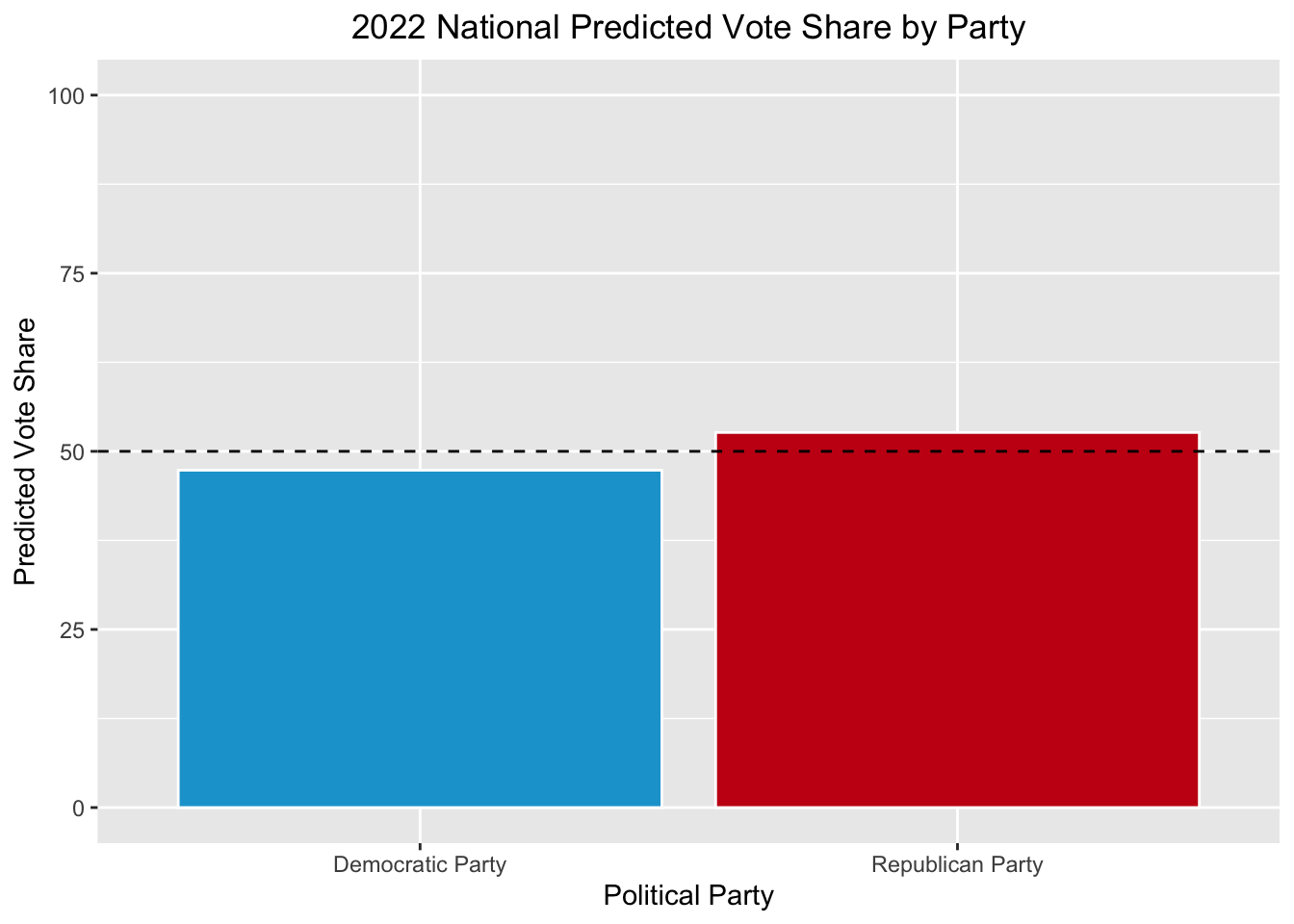

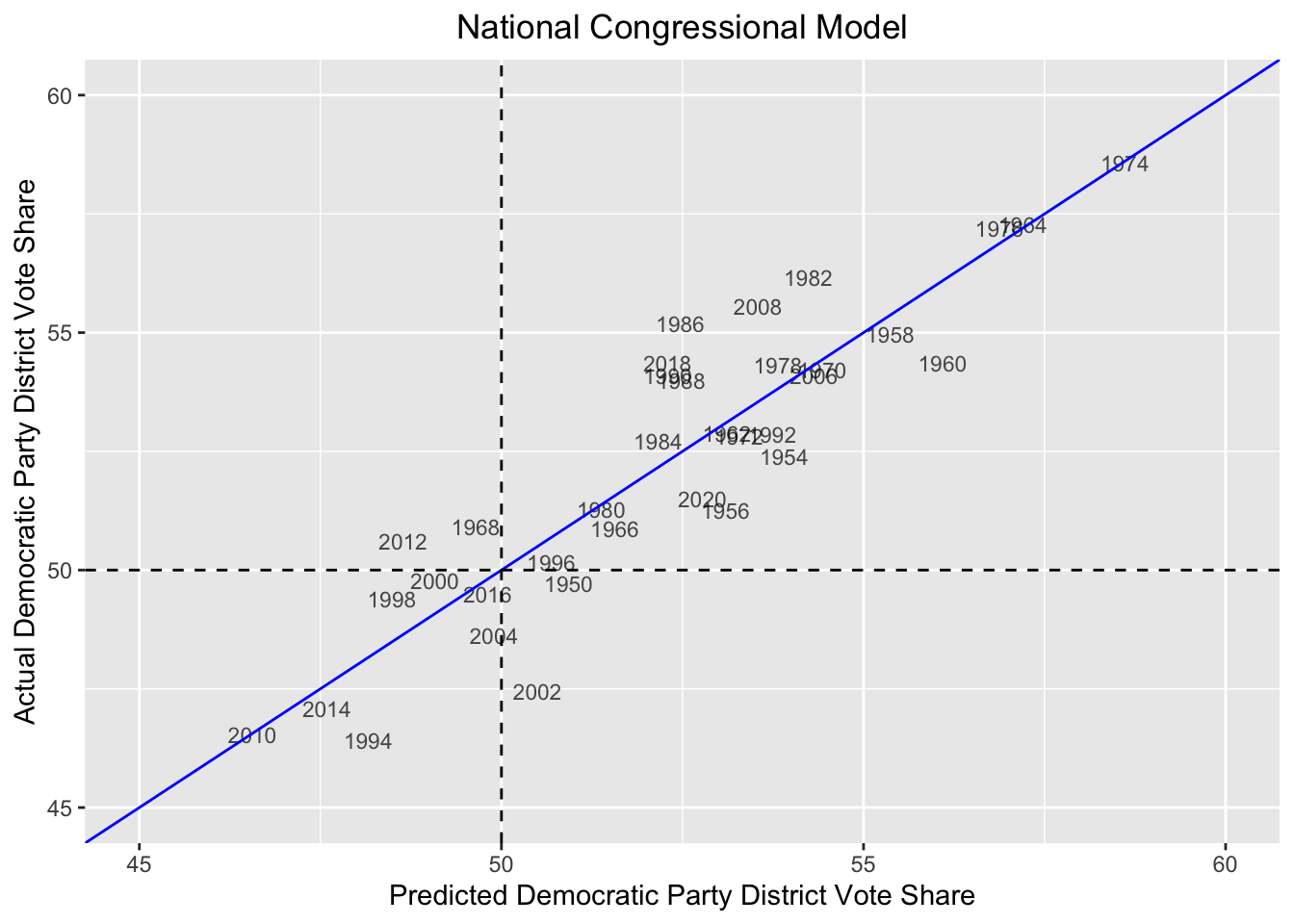

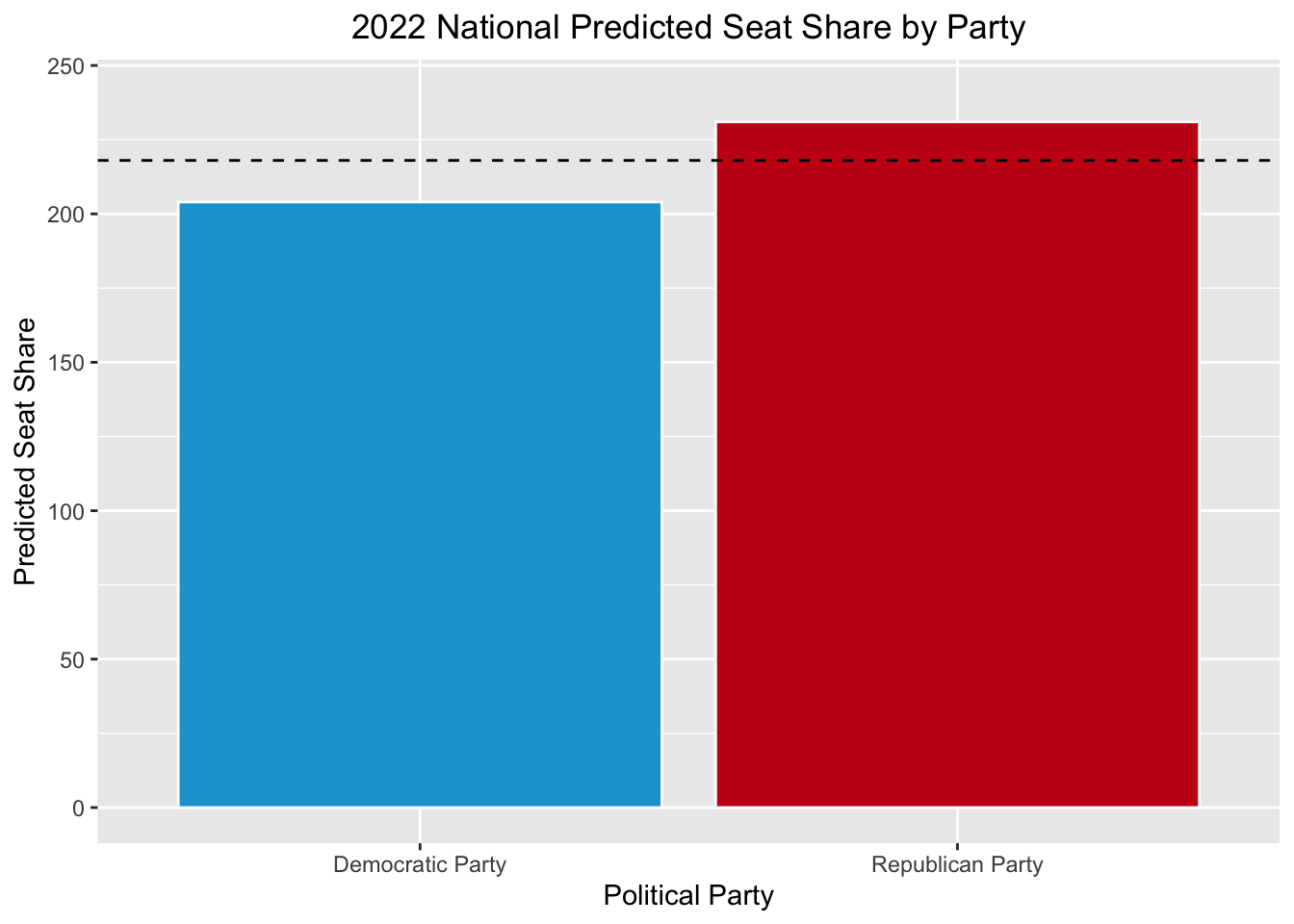

National Predictions

The first models that this blog post will examine are forecasting on a national scale. Here I will be using previously explored variables that serve as predictors for the Democratic Party’s vote share and seat share in the coming election. When predicting vote share specifically, I am using a simple unbounded linear regression model, as opposed to a GLM model that keeps the prediction between 0 and 1 (resembling 0% and 100%). In the past, I have used a GLM model, mainly because I was receiving predictions below 0% and above 100% with my linear model. However, my model has improved greatly since then, outputting predictions in-line with previous data and current forecasts by professional outlets, like FiveThirtyEight.

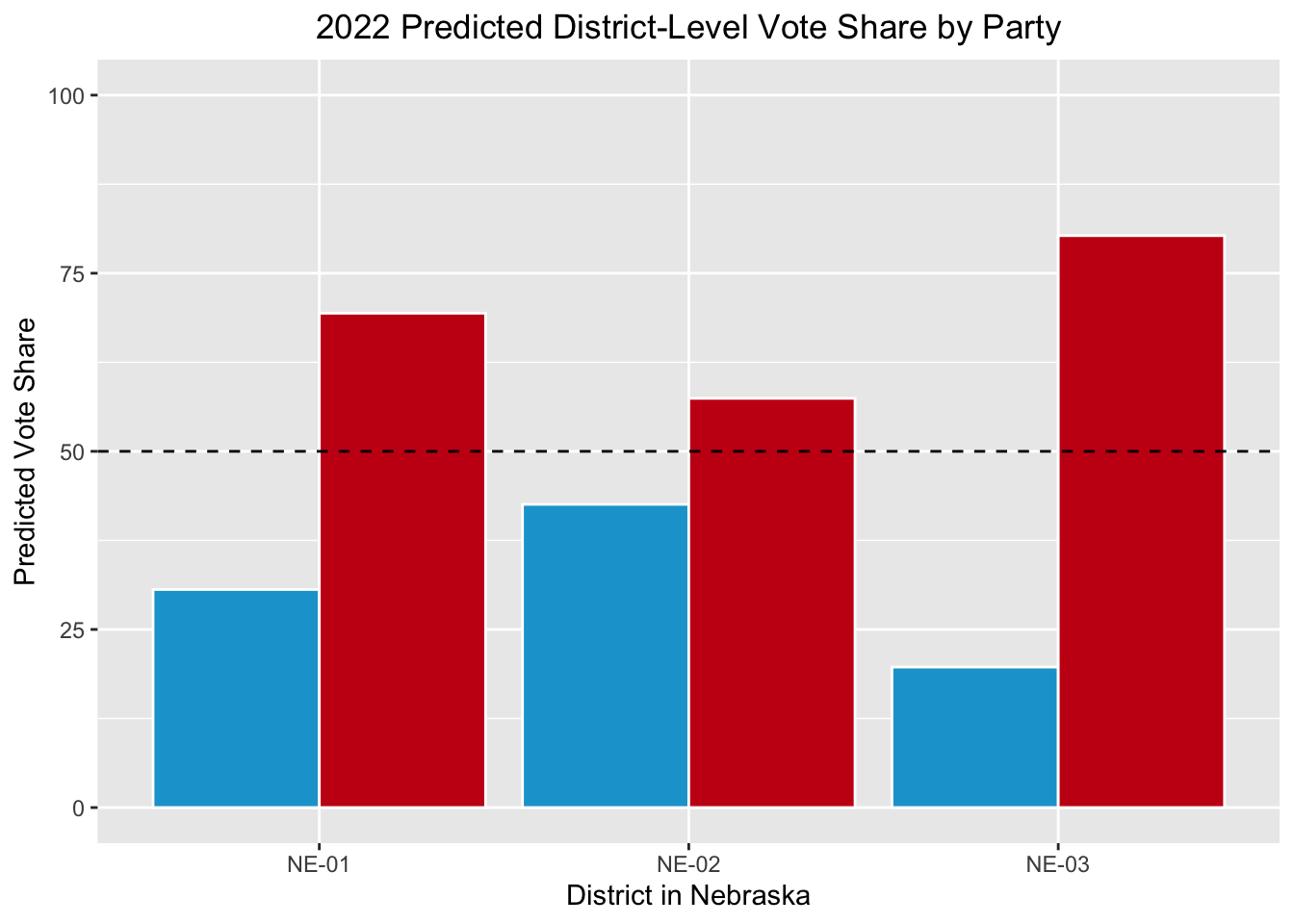

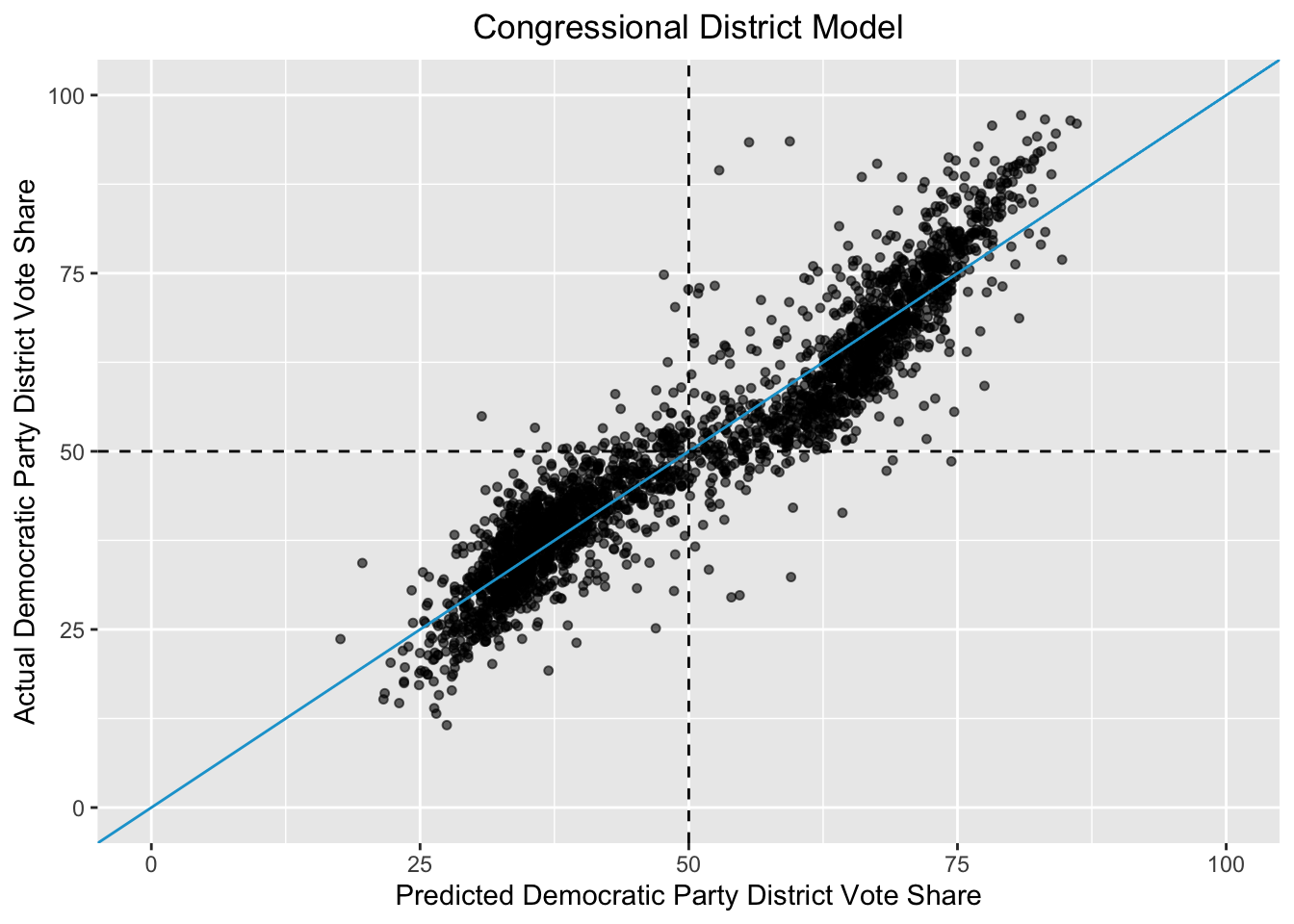

Congressional District Predictions

Next, I will move on to my district-level forecasts. In this model, I am predicted the vote share of the Democratic candidate in their particular district. What is difficult about this model is how variable data can be district-to-district. I explored this phenomenon in a previous blog post, and the crux is that many districts simply are not competitive. Lacking competition often ensures a lack of investment in and attention to the district, since the predicted winner is often known. Therefore, I will continue to use my current variables and input a powerful one: expert ratings.

Limitations

In each blog post, I have included a section on the limitations of my models, always commenting on how some variables may not be as great of predictors as one might think. However, in this section, I will take a brief and more “big picture” view.

In these models, I chose to include more national-level variables because they were more widely available and reliable than shaky data district-to-district. This allowed for me to include many more observations in my models, national and district, than I would have been able to. However, it limits the extent to which I can differentiate each district’s predictions, since national variables are the same for each district in a given cycle. Nonetheless, I believe my aggregate expert ratings and previous vote share are powerful.

Also, my model’s uncertainty in their predictions should cause some worry. Especially for the national Democratic seat share model, my prediction intervals are too wide. However, this may simply be something one has to expect in a model with only 35 observations. America is a young and unique country, and thus there are only so many elections from which to draw data. Thus, forecasting does its best to learn about voters with the data it has.

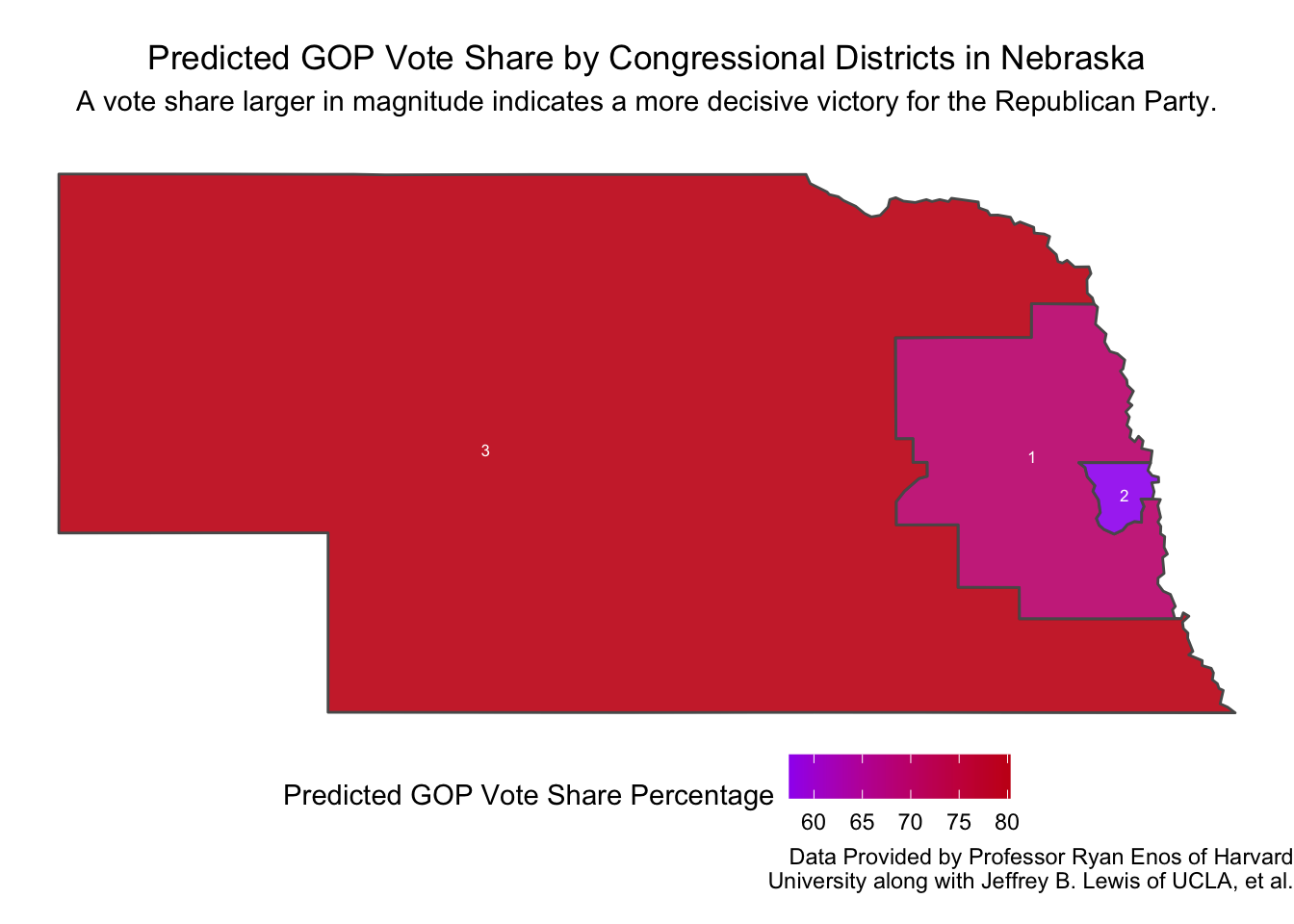

Final Nebraska Congressional District Map

To conclude this prediction blog, I will end with how I started this website: a map of my predictions for each of Nebraska’s three congressional districts. Surely enough, my predictions follow the trend of Republicans holding their ground.

Notes:

This blog is the last of a series of articles meant to progressively understand how election data can be used to predict future outcomes. I have added to this site on a weekly basis under the direction of Professor Ryan D. Enos. Tomorrow, on November 8, 2022, the midterm elections will be held. In this post, I haved used all I have learned regarding what best forecasts election results to predict the outcome of the NE-02 U.S. Congressional Election.